- Home

- Christopher Brown

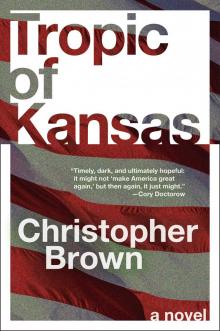

Tropic of Kansas

Tropic of Kansas Read online

Dedication

For Agustina and Hugo

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Part One: The Portages Five years later

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Part Two: Spinoza and Mortimer Snerd 13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Part Three: Prairie Fire 24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

Part Four: The Hand Made Drones 37

38

39

40

41

42

43

Part Five: Movie Nights 44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

Part Six: The Edgeland Hunters 57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

Part Seven: The Tchoupitoulas Autonomous Zone 75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

Part Eight: The Colonel and the Mastodon Queen 86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

Part Nine: The Auteur Theory of the Hostage Video 104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

Part Ten: Tropic of Kansas 113

114

115

116

117

118

119

One year later

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Advance Praise for Tropic of Kansas

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Hidden in the tall weeds of an empty lot outside Winnipeg, Sig watched the family eat dinner in the backyard of their new house on the other side of the fence. They were grilling pork chops, and it smelled good.

Sig had no house, and no food. He was hungry, dirty, and tired. He had been running for so long he forgot where he was going. Sometimes he forgot where he was from.

The kids were younger than Sig, maybe eight and ten, a redheaded boy and his dark-haired older sister. The mom was blond and the dad was bald. The lawn was an unnaturally bright green, and the picnic table was painted red. The family looked safe and happy.

The yard was filled with toys.

Sig had hopped a train in western Ontario, after a summer roaming the Quetico. The lakes were good to him until the people hunters found him, and he had to abandon the canoe he’d stolen and disappear into the woods. Now it had been a couple of days since he had a real meal, and surviving off the land was a different matter in the edges of a big city like Winnipeg. Easier and harder at the same time.

Sig watched the family for close to an hour, until they finished and went inside. The sun set, and the house glowed from the flickering white light of its electric hearth.

Sig jumped the fence and crouched behind the jungle gym, waiting to see if anyone noticed the sound of the chain link moving.

Quiet. He could hear the sounds of the family talking, and the strange voices from an interactive children’s show.

He moved to the picnic table and found the food he had seen the children drop. Part of a pork chop, and some french fries. He brushed off the dirt and ate them.

He lifted the lid on the father’s gas grill. There was some food left on there, too—three backup hot dogs. Sig ate those. They were still warm.

The sliding glass door opened. Sig ducked behind the grill. The father stepped out.

Sig watched the man scan his backyard, night blind from his house full of screens. If he could have seen Sig, he would have seen a skinny, unwashed thirteen-year-old staring back at him from under greasy, uncut bangs.

“Hello?” said the man.

A dog barked from another house nearby. Sig was glad this family did not have a dog.

The man went back inside. Sig stayed hidden. He watched and waited.

The parents carried the children upstairs. They left the television on.

Sig went to the glass door. He quietly slid it open. Listened, looked, smelled, and stepped in.

He crouched behind the sofa and scrambled to the kitchen.

There was a laundry closet there, with a hamper made of a cloth bag draped over a metal frame. Sig took the bag from the frame. It had some clothes in it. He raided the refrigerator and the pantry, filling the rest of the bag with food.

He ran out the back before the parents came back down. He forgot to close the door behind him.

Don’t look back.

He threw the bag over the fence, climbed back over, and ran off toward the woods he had come from.

Later, he built a fire in a clearing at the bottom of a ravine. He cooked frozen ravioli, and hot dogs, and marshmallows. He ate graham crackers and Cheetos and a peanut butter cup. He drank Pepsi Cola and beer. He sorted through the family’s clothes. He took a pair of the father’s blue jeans, rolled up the legs, and cinched the waist with the string from the laundry bag. He put on three of the mother’s T-shirts at the same time, and a big sweatshirt. He made a nest with the rest of the clothes, using it for bedding inside a lean-to he made under a fallen tree wedged into the muddy grade of the ravine.

Buzzed on beer, sugar, and animal fat, Sig curled up in a pile of the family’s dirty clothes and forgot about his worries for a while. Their scents were so strong and clean, he felt almost like he was living with them in their house.

The police came in the morning. They found the lean-to, but Sig had already headed farther north.

Part One

The Portages

Five years later

1

Looking at the bright blue sky from the backseat of the armored truck, which was more like a cell than a seat, Sig could almost believe it was a warm day. But the shackles around his ankles were still cold from the walk out to the vehicle, and when Sig put his head up against the bars to test for faults, he could feel the ice trying to get to him. And winter was just getting started.

“What day is it?” asked Sig.

“Deportation day,” said the big constable who had muscled him out of lockup thirty minutes earlier. When he talked the red maple leaf tattoo on the side of his thick neck moved, like a lazy bat.

“Friday,” said the Sergeant

, who was driving. “December 1. The day you get to go back where you came from.”

The thought conjured different images in Sig’s head than his jailers might have imagined.

“Back to cuckoo country,” laughed the constable. “Lucky you. Say hi to the TV tyrant for me.”

The Mounties had nicknames for Sig, like Animal and Dog Boy, but they never called him any of those to his face. They didn’t know his real name. When they trapped him stealing tools and food from a trailer at the Loonhaunt Lake work camp a month earlier, he had no ID, no name he would give them, and they couldn’t find him in their computers. They still tagged him, accurately, as another American illegal immigrant or smuggler, and processed him as a John Doe criminal repatriation. They did not know that he had been up here the better part of seven years, living in the edgelands.

The memory of that day he ran tried to get out, like a critter in a trap, but he kept it down there in its cage. And wished he had stayed farther north.

He pulled his wrists against the cuffs again, but he couldn’t get any leverage the way they had him strapped in.

Then the truck braked hard, and the restraints hit back.

The constable laughed.

They opened the door, pulled him out of the cage, and uncuffed him there on the road. Beyond the barriers was the international bridge stretching over the Rainy River to the place he had escaped.

“Walk on over there and you’ll be in the USA, kid,” said the sergeant. “Thank you for visiting Canada. Don’t come back.”

Sig stretched, feeling the blood move back into his hands and feet. He looked back at the Canadian border fortifications. A thirty-foot-high fence ran along the riverbank. Machine guns pointed down from the towers that loomed over the barren killing zone on the other side. He could see two figures watching him through gun scopes from the nearest tower, waiting for an opportunity to ensure he would never return.

Sig looked in the other direction. A military transport idled in the middle of the bridge on six fat tires, occupants hidden behind tinted windows and black armor. Behind them was an even higher fence shielding what passed for tall buildings in International Falls. The fence was decorated with big pictograms of death: by gunfire, explosives, and electricity. The wayfinding sign was closer to the bridge.

United States Borderzone

Minnesota State Line 3.4 Miles

Sig looked down at the churning river. No ice yet.

He shifted, trying to remember how far it was before the river dumped into the lake.

“Step over the bridge, prisoner,” said a machine voice. It looked like the transport was talking. Maybe it was. He’d heard stories. Red and white flashing lights went on across the top of the black windshield. You could see the gun barrels and camera eyes embedded in the grill.

“Go on home to robotland, kid,” said the sergeant. “They watch from above too, you know.”

Sig looked up at the sky. He heard a chopper but saw only low-flying geese, working their way south. He thought about the idea of home. It was one he had pretty much forgotten, or at least given up on. Now it just felt like the open door to a cage.

He steeled himself and walked toward the transport. Five armed guards emerged from the vehicle to greet him in black tactical gear. The one carrying the shackles had a smile painted on his face mask.

2

The Pilgrim Center was an old shopping plaza by the freeway that had been turned into a detention camp. It was full.

The whole town of International Falls had been evacuated and turned into a paramilitary control zone. Sig saw two tanks, four helicopters, and lots of soldiers and militarized police through the gun slits of the transport. Even the flag looked different—the blue part had turned almost black.

No one in the camp looked like a pilgrim. Instead they wore yellow jumpsuits. There were plenty of local boys in the mix, the sort of rowdies who’d have a good chance of getting locked up even in normal times. The others were immigrants, refugees, and guest workers. Hmong, Honduran, North Korean, Bolivian, Liberian. They had been rounded up from all over the region. Some got caught trying to sneak out, only to be accused of sneaking in.

They interrogated Sig for several hours each day. Most days the interrogator was a suit named Connors. He asked Sig a hundred variations on the same questions.

Where did you come from?

North.

Where specifically?

All over.

What were you doing up there?

Traveling. Hunting. Working. Walking.

What did you do with your papers?

Never had any.

How old are you?

Old enough.

Are you a smuggler?

No.

Where were you during the Thanksgiving attacks?

What attacks.

Where were you during the Washington bombings last month?

I don’t know. In the woods.

Tell me about your friends. Where were they?

What friends.

Tell us your name. Your true name.

They took his picture, a bunch of times, naked and with his clothes on. They had a weird machine that took close-up shots of his eyes. They took his fingerprints, asked him about his scars, and took samples of his skin, blood, and hair. He still wouldn’t give them his name. They said they would find him in their databases anyway. He worried they would match him to records in their computers of the things he’d done before he fled.

They made fun of his hair.

3

The improvised prison was small. A one-story mall that might once have housed twenty stores. The camp included a section of parking lot cordoned off with a ten-foot hurricane fence topped with razor wire. They parked military vehicles and fortification materials on the other side, coming and going all the time.

They rolled in buses with more detainees every day. A couple of times they brought a prisoner in on a helicopter that landed right outside the gate. Those prisoners were hooded and shackled, with big headphones on. They kept them in another section.

At night you could hear helicopters and faraway trains. Some nights there was gunfire. Most nights there were screams.

Every room in the camp had a picture of the same forty-something white guy. Mostly he was just sitting there in a suit, looking serious. Sometimes he was younger, smiling, wearing a flight suit, holding a gun, playing with kids and dogs. In the room where they ate there was a big poster on the wall that showed him talking to a bunch of people standing in what looked like a football stadium. There was a slogan across the bottom in big letters.

Accountability = Responsibility + Consequences

One of the other detainees told Sig the guy on the poster was the President.

They just tried to kill him, Samir explained. He whispered because he didn’t want them to hear him talking about it. Said people got into the White House with a bomb. Sig asked what people. Samir just held up his hands and shrugged.

Samir was the guy who had the cot next to Sig. He was from Mali. Their cot was in a pen with an old sign over it. “Wonderbooks.” There were holes in the walls and floors where once there had been store shelving. One of the guys that slept back there, a middle-aged white guy named Del, said they were closing all the bookstores on purpose. Samir said it was because no one read books anymore. Sig wasn’t sure what the difference was.

The women detainees were in a different section, where there used to be a dollar store. Sometimes they could see the women when they were out in the yard.

One day a lady showed up at Sig’s interrogation. Blonde in a suit. She said she was an investigator from the Twin Cities. Why do you look so nervous all the sudden, said Connors. They asked him about what happened back then. About other people who were with him. Sig didn’t say anything.

Looks like you get to go to Detroit, said Connors.

Sig did not know what that meant, but it scared him anyway, from the way the guy said it, and from the not knowing. He tr

ied not to show it.

That afternoon Sig found a tiny figure of a man in a business suit stuck in a crack in the floor. His suit was bright blue, and he had a hat and a briefcase. Del said there used to be a shop in the mall that made imaginary landscapes for model trains to travel through, and maybe this guy missed his train.

Del and Samir and the others talked whenever they could about what was going on. They talked about the attacks. They talked outside, they talked in whispers, they swapped theories at night after one of the guys figured out how to muffle the surveillance mic with a pillow they took turns holding up there. They talked about how there were stories of underground cells from here to the Gulf of Mexico trying to fight the government. How the government blamed the Canadians for harboring “foreign fighters,” by which they meant Americans who’d fled or been deported. They told Sig how the elections were probably rigged, and the President didn’t even have a real opponent the last time. Some of the guys said they thought the attacks were faked to create public support for a crackdown. For a new war to fight right here in the Motherland. To put more people back to work. Del said he had trouble believing the President would have his guys blow off his own arm to manipulate public opinion. Beto said no way, I bet he would have blown off more than that to make sure he killed that lady that used to be Vice President since she was his biggest enemy.

One of the guys admitted that he really was a part of the resistance. Fred said that lady’s name was Maxine Price and he’d been in New Orleans when she led the people to take over the city. He said he joined the fight and shot three federal troopers and it felt good.

Sig asked the others what it meant when the interrogator told him he was going to Detroit. They got quiet. Then they told him about the work camps. They sounded different from what he had seen in Canada. Old factories where they made prisoners work without pay, building machines for war and extraction.

On his fourth day in the camp, Sig made a knife. It wasn’t a knife at first. It was a piece of rebar he noticed in the same crack in the floor where he found the little man. He managed to dig out and break off a sliver a little longer than his finger, and get a better edge working it against a good rock he found in one of the old concrete planters in the yard. Just having it made him feel more confident when the guards pushed him around.

Failed State

Failed State Rule of Capture

Rule of Capture Tropic of Kansas

Tropic of Kansas